Originally submitted as part of research for M.S. Grad program through MSU Mankato, 2019.

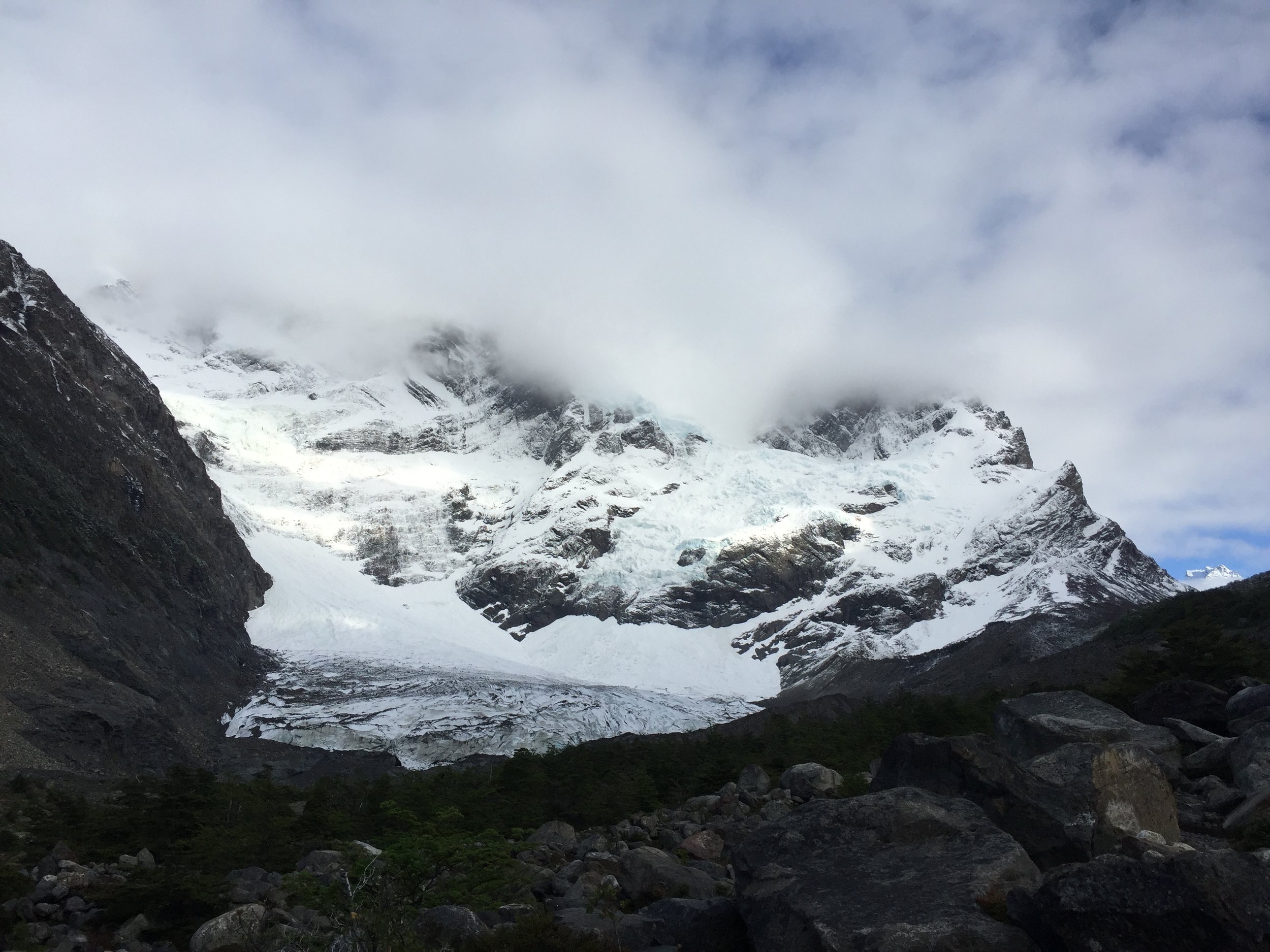

The French Valley, Torres del Paine Nat’l Park, Patagonia, Chile

Finding Clarity: Lessons in Emotional Understanding by Way of Patagonia

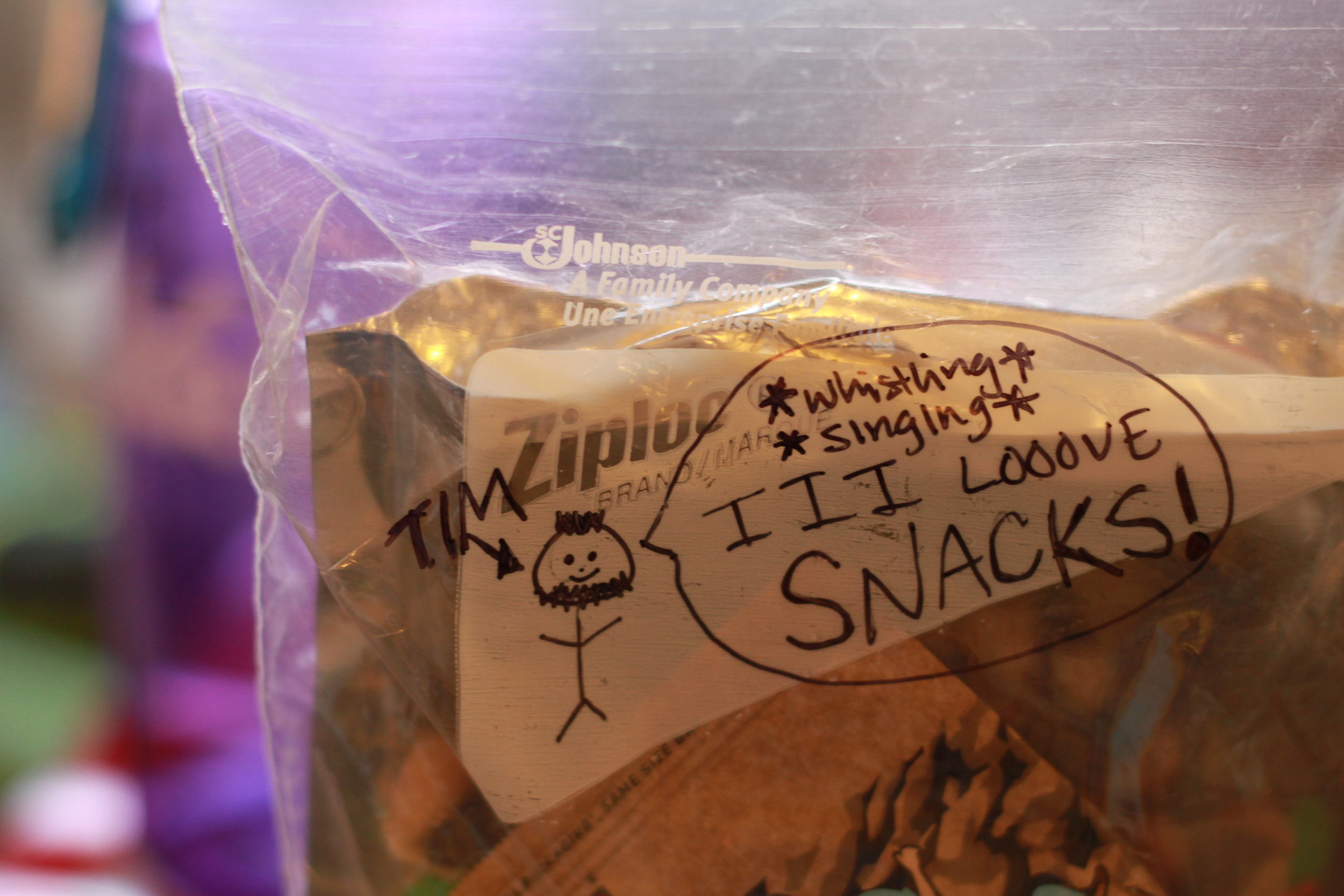

One hour before we were supposed to board the bus to take us to our starting point for a week long trek through Torres del Paine National Park in Southern Chile, we received a call from my husband’s mother. Tim’s aunt, Jackie, had lost her decades-long battle with breast cancer. It was a devastating moment, and our hearts grew increasingly heavy as we were forced to carry this overwhelming sadness from the very beginning of our hiking trip. Jackie was Tim’s biggest fan, and by sheer proximity, mine as well. She was the most supportive of us even through her struggles, and she was always inspired by our willingness to jump into unfamiliar adventure territory (like trekking through the mountains of Chile).

Our hike through Patagonia was deemed a “bucket list” item from the very beginning. We spent months planning, researching, packing, and dreaming of the trail that would (hopefully) provide us with reprieve from our over stimulating lifestyle. This trip was a chance for us to clear our minds and connect with unfamiliar and, quite frankly, intimidating terrain. What we didn’t realize was that this emotional curveball would hit us so hard that it would be the driving force for an exploration in where and how we seek out mental clarity. Death often provides an unexpected learning experience. Add in the highs and lows of time spent in the wilderness and the experience becomes a cinematic reel of overwhelming emotional and internal awakening.

My own personal desire to connect with the outdoors has long been something stronger than the need for a quick walk through the local park. Sigurd Olson captured this feeling when he wrote, “For [some], the out-of-doors is not enough; nor are the delights of meditation. They need the sense of actual struggle and accomplishment, where the odds are real and where they know that they are no longer playing make-believe. These men need more than picnics, purling streams, or fields of daffodils to stifle their discontent, more than mere solitude and contemplation to give them peace” (Olson, 2006, p. 7-8). Trips to distant places like Patagonia instinctively ignite a sense of calm for me. With the death of Jackie looming over us, every step was heavier; every overlook seemed more majestic and meaningful. We were alive and really living. We weren’t glued to our phones while walking through a fenced-off city park. Rather, the intensity of this trek provided a sense of humbling pride we couldn’t find elsewhere. This human-nature interaction we experienced taught both of us the value of giving wilderness the respect it deserves. I felt a connection—physically and spiritually—to this place I had never been before and amidst the struggle, I discovered a profound need to protect it. My time in this new place made me so grateful to be able to visit and, simultaneously, unclear as to what had to happen on this land for me to be able to access it. What I didn’t realize at the time was that my emotional confusion was due in part to a lack of what Robin Wall Kimmerer referred to as Traditional ecological Knowledge (TEK).

TEK is comprised of the understanding of indigenous and local peoples and their philosophies/relationships with the earth (Kimmerer, 2012, p.317). According to Kimmerer’s research, TEK is widely omitted in the traditional science classroom, depriving the next generations of potential ecological scientists the understanding of diverse epistemologies. He argued, “TEK, which is inherently integrative of social and biophysical processes, offers an alternative to the dominant materialist worldview which conceptually separates people from nature and instead focuses on the understanding and managing relationships between land and people for mutual benefit” (Kimmerer, p. 317).

Essentially, Kimmerer is making the point that we can’t achieve sustainability without the proper cultural awareness and understanding. He argued, “We are surrounded by the aftermath of wounds we have inflicted on the earth. We need to recognize that it is not the land which is broken, but our relationship with the land. Cultivating a relationship with the living earth should be an essential component of higher education” (Kimmerer, p. 318).

I am willing to admit that my trip to Patagonia was intended for my own selfish pleasure. The understanding of how Torres del Paine National Park (or Patagonia as a whole) came to be was not a particular priority in my early stage research, but rather an anecdote surfaced during a question and answer session with an outfitter in the small town of Punta Arenas. Patagonia’s livelihood has drastically changed over the years due to reliance on tourism as a major industry – a far stretch from its beginnings as a hub for only the hardiest of farmers (Díaz & Webb, 2018). As more people seek unique opportunities for human-nature connection, Patagonia is quick to answer with stunning untouched glaciers and towering rocky peaks unlike any other mountain range in the world. The trail is harsh and unforgiving, and we were often warned of the serious dangers and unrelenting changes in altitude. Through all of the warnings, we survived high winds and negative temperatures; sudden waves of heat followed by hours-long streaks of persistent rain. Whenever the natural world of Patagonia tried to surprise us, we challenged back with unwavering fortitude.

I tell this story often. Not to gloat, but to encourage others to seek out the sensation of experiencing the wilderness for what it is really worth: an opportunity to interact with an area that is messy, dirty, and unpredictable. Resiliency was Jackie’s superpower. She fought cancer head-on with true grace and positivity. Our trip through Patagonia became a silent salute to the woman Jackie was – fearless, strong, and endlessly optimistic. I tell this story because our relationship with nature changed drastically during this trip, as we found ourselves connecting our physical world with our spiritual world in ways we had never dreamed possible. A recent study recounted the many benefits of Nature Language and it’s impression on our interactions with the natural world. Kahn, et al. wrote, “…we think language needs to be used to articulate, save, and recover the human relationship with nature. That language–what we are calling a nature language—needs to focus not just on nature “out there,”…but in meaningful and deep forms of interactions people have with the natural world” (Kahn, et al., 2010 p. 64). The importance of our relationship with nature is that it connects us to our world as a living species. The patterns we experience such as listening to the waves crash against the beach or the sound of wind sweeping through a glacial valley will all but be lost as generations are not exposed to such natural phenomenon.

The mental clarity encountered on a long hiking trip like ours cannot be bottled up and sold online. I cannot recreate the feeling of waking up absurdly early and hiking to the top of Torres del Paine – only to be greeted by one of the most stunning multi-colored sunrises dancing across the snow-capped peaks. While many people consider us lucky to have experienced such a rare sunrise, we know deep down that the land we fell in love with and felt instantaneously connected to was reciprocating its gratitude.

References

Díaz, Emilio Fernando Gonzalez, and Kempton E. Webb. “Patagonia.” Encyclopædia Britannica, Encyclopædia Britannica, Inc., 26 Oct. 2018, www.britannica.com/place/Patagonia-region-Argentina.

Kahn, Peter H., et al. “A Nature Language: An Agenda to Catalog, Save, and Recover Patterns of Human–Nature Interaction.” Ecopsychology, vol. 2, no. 2, 2010, pp. 59–66., doi:10.1089/eco.2009.0047.

Kimmerer, Robin Wall. “Searching for Synergy: Integrating Traditional and Scientific Ecological Knowledge in Environmental Science Education.” Journal of Environmental Studies and Sciences, vol. 2, no. 4, 2012, pp. 317–323., doi:10.1007/s13412-012-0091-y.

Olson, S. “Why Wilderness?” The View From Listening Point Newsletter, vol. VIII, no. 4, Fall/Winter 2006. Retrieved from https://listeningpointfoundation.org/wp-content/uploads/2012/03/VFLP_Winter_2006.pdf.